You’ve heard of wireless standards like Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and 5G. Now it’s time to learn about another: ultra wideband, or UWB.

The technology, which has begun arriving in phones, tracking tags and a few cars, uses radio signals to pinpoint a device’s location. UWB is the foundation of tracking tags like Apple’s AirTag and Samsung’s SmartTag Plus, which can help you find a lost keychain, purse, wallet or pet. In a few cases, like the like the BMW iX, UWB lets you unlock your car as you approach with your phone, and it should let you do so with your home’s front door, too.

UWB calculates locations to within less than a half inch by measuring how long it takes super-short radio pulses to travel between devices. It can also transfer data — indeed, that’s what it was originally designed to do more than a decade ago — but for now, that’s a sidelight compared to precise positioning.

For now, UWB’s uses are limited. But as it matures and spreads to more devices, UWB could lead to a world where just carrying your phone or wearing your watch helps log you into your laptop as you approach or lock your house when you leave.

Apple is one of the biggest UWB fans. It designed its own UWB chip, the U1, and builds it into iPhones, AirTags and Apple Watches. That’s how newer iPhones use “precision finding” to lead you to an an AirTag-equipped keychain or Apple Watch within range. Carmakers including Audi, BMW, Hyundai and Ford are hot for UWB, too.

“Being able to determine precisely where you are in an environment is increasingly important,” said ABI Research analyst Andrew Zignani, who expects shipments of UWB-enabled devices to surge from 150 million in 2020 to 1 billion in 2025. “Once a technology becomes embedded in a smartphone, that opens up very significant opportunities for wireless technology.”

Post Contents

What’s UWB good for?

Satellite-based GPS is useful for finding yourself on a map but struggles with anything much more precise and indoors. UWB doesn’t have those handicaps. But UWB’s potential goes far beyond that practical feature.

UWB could switch your TV from your child’s Netflix profile to yours. Your smart speaker could give calendar alerts only for the people in the room. Your laptop could wake up when you enter the home office.

Imagine this scenario: You leave the office and as you near your car, receivers in its doors recognize your phone and unlock the vehicle for you. When you get out of the car at home, the receivers recognize you’re no longer in the vehicle and lock the doors.

With UWB, your home could recognize that you’re returning at night and illuminate your walkway. It could then automatically unlock your front door. Your music and lights could follow you from room to room.

“I’m walking in a sound and light cocoon in my house,” said Lars Reger, chief technology officer of NXP Semiconductors, a UWB proponent whose chips are widely used in cars.

Screenshot by Stephen Shankland/CNET

Bluetooth-based location sensing takes at least two seconds to get an accurate fix on your location, but UWB is a thousand times faster, Reger said.

UWB will add more than convenience, supporters say. Conventional key fobs have security problems in regard to remotely unlocking cars: criminals can use relay attacks that mimic car and key communications to steal a vehicle. Case in point: security researchers at NCC Group demonstrating in May they could hack into a Tesla Model 3’s Bluetooth connection. Tesla told the researchers that such relay attacks are a known limitation.

UWB has cryptographic protections against that sort of problem. And Tesla, for one, is interested. UWB’s precise timing and positioning technology means it’s “immune to relay attacks,” the carmaker said in a 2021 application with the FCC for new wireless key fobs and in-car equipment seen by the Verge.

This same ability to track your movements has downsides, particularly if you don’t like the idea of the government following your movements or coffee shops flooding your phone with coupons as you walk by. But with today’s privacy push, expect phone makers to prohibit anyone from tracking your phone without your permission.

How is Google supporting UWB?

Google’s support for UWB began in 2021 with its Pixel 6 phones. But the company’s influence is greater through its Android phone software.

Google added limited UWB support into Android 12 in 2021, but it should improve with Android 13 in 2022. That’s because the company is opening up the programming interface so any app can use it, not just Google’s software. Google also is adding UWB support to Android’s Mainline technology that could spread UWB support so apps can use it on earlier phones, too.

Google’s UWB support enables digital car key technology so you will be able to use your phone as a car key on some BMW models. Android can store digital car keys in Google Wallet. Expect broader support among carmakers in coming years.

How is Apple supporting UWB?

The iPhone 11, iPhone 12 and iPhone 13 smartphones include Apple’s UWB chip, the U1. It joins a handful of other processors Apple has developed, including the A series that powers iPhones and iPads, the M1 at the heart of new Macs, iPad Pros and iMacs, and the T series that handles Touch ID and other security duties on Macs.

Credit: Apple/Screenshot by CNET

AirTags really bring the technology alive, though. UWB communicates with an iPhone 11 or 12 so a big arrow leads you to the tag. When UWB isn’t in range, a Bluetooth connection means AirTags tap into Apple’s Find My system, which lets other people’s devices discover your AirTag’s location and share it privately with you.

“The new Apple-designed U1 chip uses ultra wideband technology for spatial awareness — allowing iPhone 11 Pro to precisely locate other U1-equipped Apple devices. It’s like adding another sense to [the] iPhone,” Apple said of the U1 chip when it arrived. Here’s another use: “With U1 and iOS 13, you can point your iPhone toward someone else’s, and AirDrop will prioritize that device so you can share files faster.”

The Apple Watch Series 6 and Series 7 also have UWB built in to make them easier for you to locate.

Apple only promises UWB links between its own devices for now. But UWB standardization should open up a world of other connections, and software tweaks should let Apple adapt as UWB standards mature.

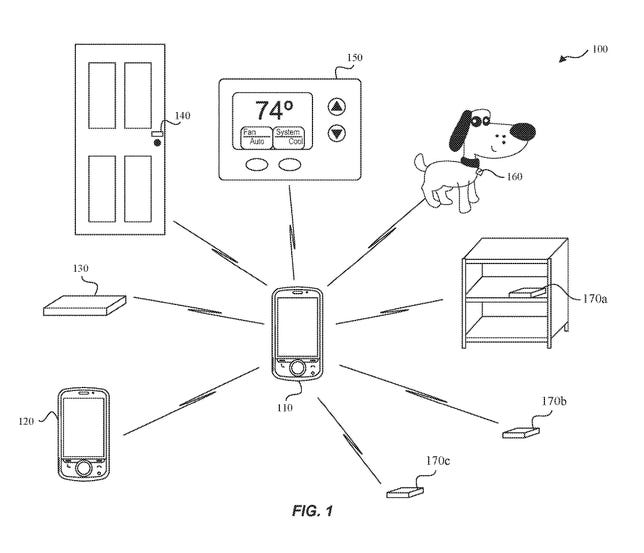

Apple’s years of UWB work are evident in several patents. That includes patents for shaping UWB pulses for more accuracy in distance measurements, using a phone, watch or key fob location to enter and start a car, calculating your path toward a car so your car can send your phone a request for biometric authentication, and letting Bluetooth and UWB cooperate to grant you access to your car.

Apple via US PTO

How is Samsung supporting UWB?

Samsung supports UWB in its Galaxy Note 20 Ultra, Galaxy S21 Plus and Galaxy S21 Ultra, and Galaxy S22 smartphone family.

“You’ll be able to unlock your car door with your phone,” said Kevin Chung of Samsung’s direct-to-consumer center during the S21 2021 launch. “The door will unlock when you reach it — no sooner, no later.”

Samsung’s UWB-based digital car key technology lets you send digital keys to friends or family members, and Samsung’s AR finder app will point the direction to your car in a crowded parking lot. Samsung has digital key partnerships with BMW, Audi, Ford and Hyundai’s Genesis Motor.

Samsung SmartTag Plus uses UWB.

Who else is interested in UWB?

Other companies involved with UWB include consumer electronics giant Sony; chipmakers Decawave, Qualcomm, NXP and STMicroelectronics; carmakers Volkswagen, Hyundai, and Jaguar Land Rover; and car electronics powerhouse Bosch.

Another notable player is Tile, which has sold tracking tags for years to help you find things like keychains and wallets. The UWB-based Tile’s Ultra was due in early 2022, but Life360 acquired the company and is reviewing product launch timing. It still plans to ship the Tile Ultra “when the time is right for the combined company,” a Tile representative said in a statement.

Confusingly, those companies have banded together into two industry groups, the UWB Alliance that formed in December 2018 and the FiRa Consortium (short for “fine ranging”) that formed in August 2019. Samsung joined FiRa, Apple isn’t listed as a member of either.

On top of that, there’s the Car Connectivity Consortium that’s working on digital key technology. The three groups have figured out who’s doing what now to avoid stepping on each other’s toes, Harrington said.

FiRa is working on standards to ensure UWB devices work together properly, while the UWB Alliance is trying to minimize UWB problems from the expansion of Wi-Fi into the 6GHz radio band that UWB also uses. For example, there are brief pauses in Wi-Fi signals sent in the 6GHz band, and UWB transmissions could sneak into those gaps, said UWB Alliance executive director Tim Harrington.

How does UWB work?

The idea behind UWB has been around for decades. Indeed, the University of Southern California established an ultra wideband laboratory called UltRa in 1996. Some of the concepts date back to radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi, Harrington says.

UWB devices send lots of very short, low-power pulses of energy across an unusually wide spectrum of radio airwaves. UWB’s frequency range spans at least 500MHz, compared with Wi-Fi channels often about a tenth as wide. UWB’s low-power signals cause little interference with other radio transmissions.

UWB sends up to 1 billion pulses per second — that’s 1 per nanosecond. By sending pulses in patterns, UWB encodes information. It takes between 32 and 128 pulses to encode a single bit of data, Harrington said, but given how fast the bits arrive, that enables data rates of 7 to 27 megabits per second. Tesla could be interested in UWB’s data transfer abilities, promising speeds up to 7.8Mbps.

Screenshot and illustration by Stephen Shankland/CNET

The IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers) developed a UWB standard called 802.15.4 more than 15 years ago, but it didn’t catch on for its original intended use, sending data fast.

Location sensing made UWB a hot topic again?

Companies like Spark Microsystems use UWB for data transfer, but most tech giants like it for measuring location precisely. Even though 802.15.4 flopped when first created years ago, UWB’s renaissance is occurring because its super-short radio pulses let computers calculate distances very precisely.

Now UWB development is active again, for example with the 802.15.4z standard that bolsters security for key fobs and payments and improves location accuracy to less than a centimeter. Fixing today’s relay attack problems, where someone with radio technology essentially copies and pastes radio communications of key fobs or smartphone unlocking systems, was a top priority for 802.15.4z. “With the precise timing you get off UWB and the ability to know exactly where you are, you can cut the man in the middle [relay] attack completely,” Harrington said.

Another area of active development is improving how you can use your phone to make payments at a payment terminal.

Radio waves travel about 30 centimeters (1 foot) in a billionth of a second, but with short pulses, devices can calculate distances very exactly by measuring the “time of flight” of a radio signal to another device that responds with its own signal. With multiple antennas positioned in different spots, UWB radios can calculate the direction to another device, not just the distance.

UWB dovetails nicely with the internet of things, the networking of doorbells, speakers, lightbulbs and other devices.

It’s already used for location sensing. NFL players have UWB transmitters in each shoulder pad, part of broadcast technology used for instant replay animations. A football’s location is updated 2,000 times per second, according to Harrington.

Boeing uses UWB tags to track more than 10,000 tools, carts and other items on its vast factory floors.

UWB uses very little power. A sensor that sends a pulse once every second is expected to work for seven years off a single coin battery.

Verizon has 5G Ultra Wideband. Is that the same thing?

No. Verizon uses the same words, but it’s merely a branding label.

“5G Ultra Wideband is our brand name for our 5G service,” said spokesman Kevin King. “It’s not a technology.”