Apple just took another step on its one device quest.

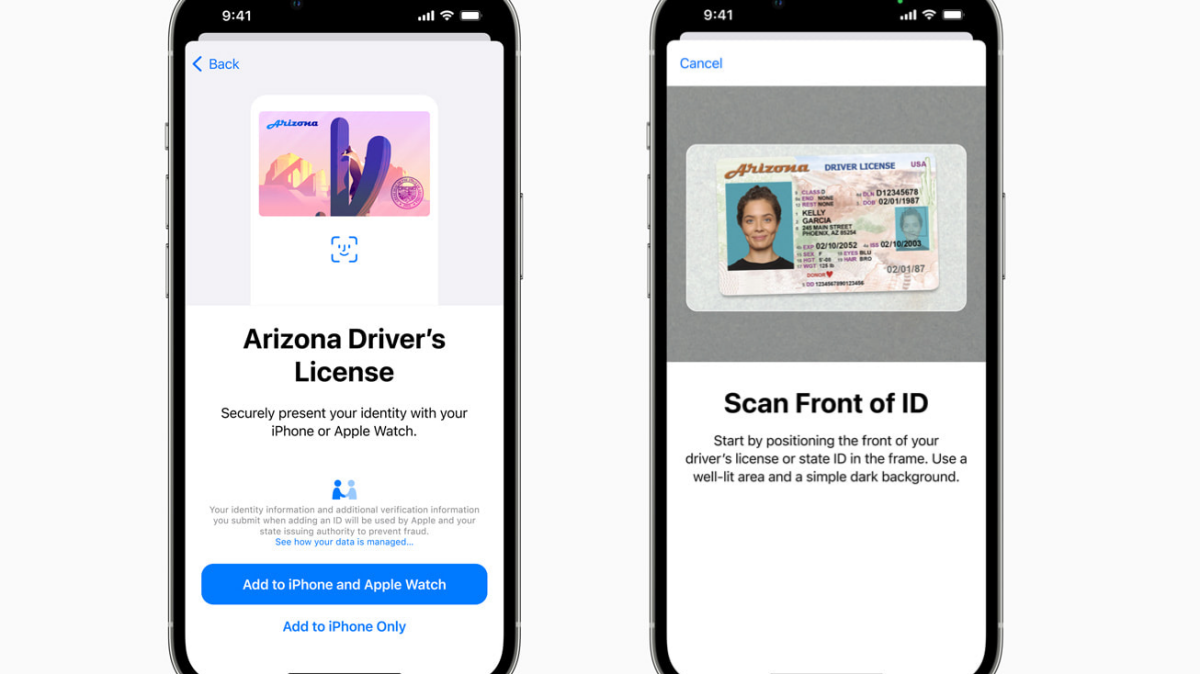

The tech giant announced Wednesday that, starting immediately, iPhone owners in Arizona will be able to add their government-issued IDs or driver’s licenses to their Apple Wallets and use the digital copies in lieu of a physical one with TSA officials at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport. Arizona is just the first state of many that Apple said it has queued up for its digital IDs — a promise that brings with it its own set of potential privacy concerns.

“We’re thrilled to bring the first driver’s license and state ID in Wallet to Arizona today, and provide Arizonans with an easy, secure, and private way to present their ID when traveling, through just a tap of their iPhone or Apple Watch,” Jennifer Bailey, Apple’s vice president of Apple Pay and Apple Wallet, is quoted as saying in the press release. “We look forward to working with many more states and the TSA to bring IDs in Wallet to users across the US.”

Up next, according to Apple, are Colorado, Hawaii, Mississippi, Ohio, Puerto Rico, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Oklahoma, and Utah.

Alexis Hancock, the director of engineering at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, expressed reservations about Apple’s plans.

“The main privacy concern I have is how ‘digital first’ will overlook the scenarios in the near future where people don’t want to tie identity documentation to their devices if they do not wish to,” she explained over email. “Convenience value is certainly provable here,” she conceded, but she worried that the TSA or other enforcement entities “may overstep with this technology.”

Notably, Apple first shared its plans to let iPhone owners store their IDs inside the iOS Wallet app way back in June of 2021. In September of that same year, the company said state ID’s from Arizona and Georgia would be the first to be accepted by the Wallet app. Wednesday’s announcement makes clear that the corporate push away from physical IDs is moving forward, and that the TSA will actually accept the Apple Wallet ID (at least in Arizona).

Apple took pains to insist that it had, in fact, thought through any and all privacy concerns associated with turning one’s phone — the same device which contains banking details, personal email and texts, photos, health data, physical location data, and internet browsing history — into one’s form of ID.

For example, to users who may not want to hand over their unlocked phone to officials, Apple assured readers no hand-off would be required.

“On their iPhone or Apple Watch, users will be shown which information is requested by the TSA, and can consent to provide it with Face ID or Touch ID, without having to unlock their iPhone or show their ID card,” read the announcement. “All information is shared digitally, so users do not need to show or hand over their device to present their ID.”

This assumes every official demanding to see someone’s ID is acting in good faith, and, that even if they are, somehow sharing the contents of one’s smartphone with that official is anything other than a risky proposition.

“Apple made a way where you don’t have to unlock your phone, which is an ideal privacy-preserving feature,” added Hancock. But she pointed to worrying situations like, “being forced to unlock your phone, having your phone taken, or [being] coerced into tapping your device and prove your identity,” as potential future vulnerabilities.

If the use cases for putting government ID into Apple’s Wallet app ever expand, iPhone owners trying to tell a police officer that, no, they don’t need to hand over their smartphone because Apple developed a process for securely and remotely sharing credentials digitally may find themselves in a tight spot.

And law enforcement is, of course, able to access the contents of many locked iPhones.

“I want people to have nice things,” concluded Hancock. “But there’s a lot of factors in a digital first world we have to consider at each step.”

Apple is asking users to trust that it has, in fact, done all the considering that is necessary.