Better representation, inclusivity and accessibility would mean great things for the gaming industry.

gorodenkoff/Getty Images

This story is part of The Year Ahead, CNET’s look at how the world will continue to evolve starting in 2022 and beyond.

Imagine hanging out with a large group of friends in a room. As you laugh, catch up and check in with each other, the door flies open and a swarm of strangers shove their way in. They’re yelling over each other, drowning out your conversation with your friends. It’s all happening so fast, you can only catch bits of what they’re saying — calling you names, saying they’ll do horrific things to you, disparaging your ethnicity and your gender. You can’t hear your friends anymore. Your stomach twists and your palms sweat. You want to hide. You want to leave the room. Your safe space has been violated. You’ve just been hate raided on Twitch.

Raven started streaming on Twitch after a former partner told her she couldn’t do it. She now has a Twitch following of 5.7K.

RekItRaven

Hate raids happen when bots and real accounts flood a chat with hateful, abusive rhetoric, and they can happen to anyone without warning. After two weeks of being targeted by these raids, Twitch streamer RekItRaven decided to take a stand and started #TwitchDoBetter. She later teamed up with fellow streamers ShineyPen and Lucia Everblack for #ADayOffTwitch, a one-day strike demanding the platform take action against the escalating hate raids, doxxing and other abuse.

“After seeing countless Black and Brown people endure so much hardship, inequality and injustice and really focusing on politics I knew that I could use my voice to do something,” Raven told me in an email. “Hate raids weren’t new but the frequency in which they expanded to all corners of Twitch where marginalized people were was something I’ve not seen in my career on this platform.”

Raven’s experiences don’t exist in a vacuum. According to a 2021 report from the Anti-Defamation League, 83% of adults and 60% of young people surveyed experienced harassment in online multiplayer games. Instances of severe abuse, including physical threats and stalking, increased in 2019 and 2020.

Over the past year more and more people have helped pull back the curtain on deep-rooted problems in the gaming industry, as well as individual communities such as Nintendo’s Super Smash Bros and Minecraft. Well-known companies including Riot Games, Activision Blizzard and Ubisoft have come under scrutiny for allegations of sexual misconduct, harassment and other discriminatory behavior in the workplace.

“We’re in this beautiful age where people are really starting to understand that complacency is no longer accepted and that people — no matter how small — can raise their voice and create a movement,” Raven said.

Raven, her fellow Twitch streamers and others in online gaming spaces are no longer accepting the decades of unchallenged sexism, racism, shallow stereotypes and discrimination that have shaped the gaming world we know today.

Past and present Blizzard Activision employees took part in a walkout over CEO Bobby Kotick’s response to allegations of sexual harassment and discrimination in the company.

Bloomberg/Getty Images

When you Google “gamer,” most of the images will be of young, white men playing video games, their faces bathed in light from an elaborate computer setup, brows creased in concentration. The gaming industry has a history of creating one-size-fits-all content, but anyone who doesn’t immediately fit the profile of a white, able-bodied, cisgender man faces an obstacle course laden with threats, violence, othering behaviors and harassment.

Peeling back the layers to find the root causes of the problems in the gaming industry is a daunting task, but Raven and her fellow Twitch streamers, as well as others in online gaming spaces see the gaming world’s recent reckoning as potential for real change. Here’s why it’s vital that a safer, more accessible and representative industry become the standard in 2022, as told by the people who are working to build it.

Post Contents

Redefining the image of a gamer

Lara Croft’s original hypersexualized character design from 1996.

Steam/Screenshot by CNET

Pong and Computer Space, two of the first video games in the ’70s, sidestep issues of gender because their characters are lines and dots. The ’90s, however, introduced a hypersexualized depiction of female characters in games, according to Indiana University media communications researcher Teresa Lynch. The decade ushered in the laughably proportioned Lara Croft and Ivy Valentine. The gaming industry seemed to plant its flag as a proud member of the boys’ club.

Fortunately, women have gotten better representation in games more recently. Though not a perfect system, more of today’s games star strong, complex female characters with agency, including Ellie in the Last of Us, Marianne in The Medium and Billie Lurk in the Dishonored franchise. You also have the option to play as a female character in games like Assassin’s Creed.

Ellie brought depth to both Last of Us games.

Naughty Dog

Although women make up almost half of the gaming audience, representations of women in many games remain narrow and unrealistic. The enlarged busts and hips, pencil-thin waists, as well as a lack of clothing and personality, doesn’t reflect the women playing the games — and those women take notice.

Twitch streamer Kedapalooza calls her channel Camp Kedapalooza, a space for some 3.7K followers to escape everyday stresses. This past spring, Keda received a BroadcastHER grant from the 1,000 Dreams Fund, a national nonprofit organization that seeks to empower young women.

“All of my life I was made fun of and seen as less than because of my size,” Keda told me in an email. “For a lot of people, my size dictated my worth, my potential, my productivity. Fat women are usually seen as the punchline, the funny best friend [or] the support roles.”

Kedapalooza learned to embrace her identity after finding representation online.

Kedapalooza

When Keda started college, she began discovering content creators that she could see herself in, which inspired her to be more confident in her own identity. As Keda embraced herself more, the positivity spread to her online following.

“I want other Black, fat, queer people to know that they don’t need to lose weight or change anything about themselves to chase their dreams,” Keda said. “You can start now. You are and always will be the main character of your own story.”

Historically, black and queer characters were present only as caricatures in video games, if they were present at all. For decades, video games pigeonholed Black characters as athletes or ne’er-do-wells in the inner-city — a far cry from the beloved protagonist of Spider-Man: Miles Morales. A demographic’s depiction in the media can affect how, and sometimes whether, those people are seen in real life.

Life of Strange included queer storylines in the first two games.

GameSpot

Finding queer characters in video games was a revelation to me as a bisexual woman. In 2015, my favorite point-and-click mystery game franchise released Nancy Drew: Sea of Darkness, which featured an LGBTQ character. That same year, I saw LGBTQ representation in the choice-based game Life is Strange. The ability to play as a man or woman in Fallout 4 fascinated me — especially because the game treated those characters equally, no matter which gender you chose — as did the options to romance same-sex characters. Later, Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate and Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey presented Evie Frye and Kassandra, respectively, as brave, complex playable characters, instead of the franchise’s historically male protagonists.

In Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate, Evie was a playable character with her own specific skills and abilities.

CNET

The representation of intersectional identities has come a long way, but there’s still work to be done. In the meantime, some content creators are actively creating representation, rather than waiting to see themselves in media.

ItsGapped strives to help others grow their confidence by being unapologetically his most authentic self.

ItsGapped

On his Twitter page, content creator ItsGapped has a pinned tweet for new followers to get to know him. In the 12-second clip, he greets viewers and tells them that he’s gay. When Mixer closed down, Gapped considered moving his platform to Twitch, but the horror stories from other creators about the toxicity on the platform gave him pause. What hateful treatment would he encounter? Was it even worth it? Like Keda, Gapped drew on strength from other like-minded content creators on the platform. He now streams games like Pokemon, League of Legends and Dead by Daylight for 4.2K Twitch followers.

“If they could withstand the trolls on [Twitch], I firmly believed I could too,” Gapped said. “The things that kept me streaming was the community I made and the people I’ve met on the platform.”

As Gapped’s follower count climbed, he too received grateful messages from viewers for providing representation and nurturing a safe space online.

“I was inspiring some people to be more confident in themselves due to how unapologetic I was about who and what I am,” Gapped said. “I realized as a streamer, just being in the space as a minority is making a change. Just by me being black and queer I’m pushing the norm. I am happy to be able to make a change just by existing and telling my story.”

Making games more accessible

The number of active video gamers has been rising steadily since 2015, according to Statista. In 2020, Statista reported 2.69 billion gamers with the number expected to grow to over 3 billion by 2023. Gamers come in all shapes, sizes, colors and ages, and the gaming industry must reflect that.

Brandon Cole speaking at the first Game Accessibility Conference in 2017.

IGDA GASIG/Screenshot by CNET

Brandon Cole, an Ohio-based accessibility consultant for Aquent Games, always loved video games, but being completely blind meant that, instead of playing for himself, he spent more time listening to others play. But, with the help of his fiancee, he set out to change that. Cole’s website, where he shares ideas for making video games more accessible, soon gained attention.

After taking the stage at the first ever Game Accessibility Conference in 2017, Cole caught the attention of Naughty Dog representatives, who were at his panel. Naughty Dog is the game company behind hit franchises like The Last of Us and Uncharted. Cole chatted with the studio representatives after his presentation. A few weeks later, plans to fly him out to the studio were in place. From there, Cole had a hand in making sure The Last of Us Part 2 was released with more than 60 accessibility settings and features that will make it easier for people with vision, hearing and fine motor skill disabilities to play.

Cole says it’s important for game developers to work with consultants for better accessibility and representation in games. While there are accessibility guidelines for developers, Cole says they might not be enough.

And Cole is right. Disabilities can happen to anyone at any time, and aging — even for this digital generation — is inevitable. The World Health Organization reported more than 1 billion disabled people in the world in 2021. In addition, WHO reported that the number of people with disabilities is increasing because of “demographic trends and increases in chronic health conditions.”

A look at The Last of Us visual accessibility features Brandon helped develop.

Can I Play It/ Screenshot by Shelby Brown/ CNET

Cole sees promise in the future of gaming accessibility, and he says the conversations are happening, citing higher accessibility conference attendance, as well as more accessibility panels and segments in mainstream gaming conferences.

“It’s definitely a long road because accessibility is not an easy thing to do,” Cole said. “I think more developers are starting to become more receptive to it little by little. I think we’ll get there.”

Queerlybee is an advocate for marginalized individuals in the gaming community and everyday life.

Queerlybee

Up in Wisconsin, gamer Queerlybee (or Bee) found themselves searching for a community with other disabled and queer people. When the pandemic hit, Bee struggled to adapt to life away from Syracuse University in New York. They decided to make their own community by streaming games on Twitch.

Bee is no stranger to fighting for change. During their time in college, they advocated for marginalized students. When it comes to improving the state of gaming, Bee says that representation in spaces where decisions are made is vital.

“Games and gaming content can be vastly improved by introducing different voices and experiences,” Bee said. “Marginalized folks and creators are just humans like anyone else and we want the opportunity to pursue things we are passionate about without necessarily being a token. We are creating spaces for future generations of marginalized folks to be able to enter this space and industry without facing so many constant microaggressions and questioning their worth and value in the space.”

Creating new spaces for 2022

Unfortunately, even with streamers trailblazing change, harassment persists. The ADL cited identity-based harassment as a problem for young gamers identifying as Black or African American, female and Asian American. In the report, 74% of women, Black, Asian American, and LGBTQ gamers said they hide their identities while gaming.

Jill Kenney and Stephanie Peloza sought to change that by building an entirely new platform to give people the chance to be their authentic selves without fear of harassment.

“It was very clear that the gaming industry was built from the ground up by men for men and that not only were women being left out of the conversation, they were also being severely harassed when they turned their mics on when playing, and I am just not OK with that,” Kenney told me. “It is time for change.”

Kenney, Peloza and their team launched Paidia, a safe gaming community for women and allies of all genders on Nov. 10.

Paidia is a female-focused gaming portal where women and allies can play online games without fear of harassment.

Paidia

Peloza — whose Paidia-exclusive podcast Move Makers spotlights women in the gaming industry — was drawn to the concept of Paidia after a lifelong struggle trying to participate in the gaming community as a woman.

“Throughout the different stages of my life, I’ve experienced gatekeeping or exclusion from gaming in different ways,” she told me. “Even so far as being laughed out of a nerd culture store when I was 19, and repeated, consistent, and disconnected incidents of harassment in World of Warcraft. This pattern is present across many genres, but none so much as competitive gaming and in particular, [first person shooters], which has been generally regarded as a boys’ club for decades.”

Peloza, a fan of the Halo franchise, began limiting herself to the campaigns and player-versus-environment game modes because of experiences with toxic gaming in player-versus-player environments. Even if you’re not targeted for speaking up as a woman in a game or using a feminine gamer tag, toxicity still runs rampant in the form of name-calling, rage and slurs, according to Peloza.

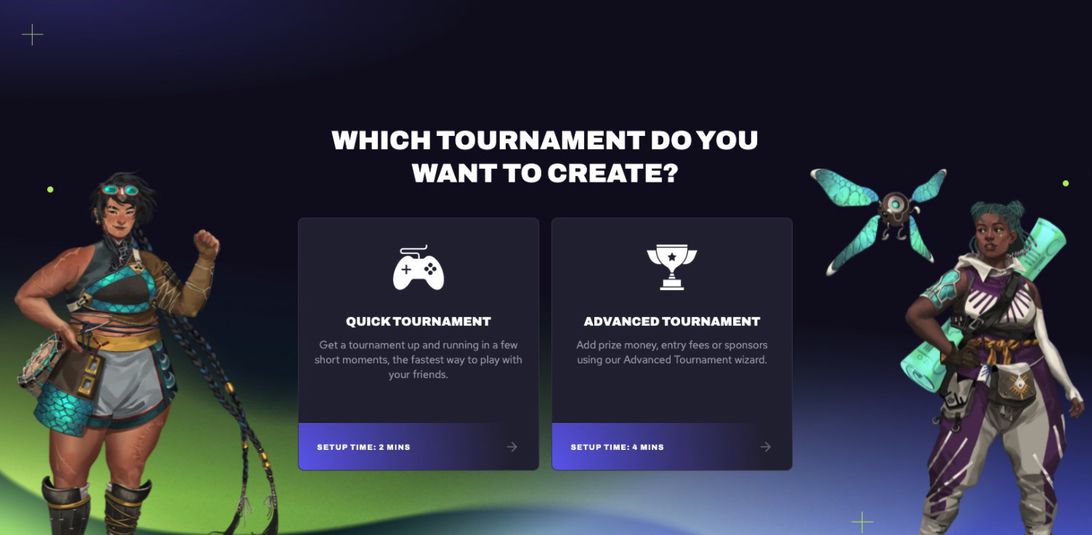

Paidia tries to cut off the problem from the start. When you sign up, you’re prompted to take an acceptance pledge condemning online harassment and abuse of any kind. Kenney calls the Paidia Pledge the portal’s first line of defense.

When I spoke with Jill Kenney and Taylor Sudermann, Paidia’s director of digital products, they walked me through Paidia’s beta portal last month. But talk of tournaments and esports made me nervous. I’d never gotten into esports or social multiplayer games — the horror stories of online harassment and abuse against women had done its damage. It was too late for me to learn. Or, at least, that’s what I thought.

“The barrier is not women’s skill level, it’s the established culture,” Peloza said. “This culture came from such a meaningless place, too.”

Peloza means that video games and their marketing weren’t originally so slanted towards men. When trying to pinpoint exactly when video games became viewed as more of an activity for boys, a 2017 report from GameLuster cited the gaming crash in 1983 that left companies scrambling to find a demographic to mend their profit. When an industry desperately trying to staunch its bleeding bottom line collides with the archaic concept of gendered toys, the Nintendo Game Boy is born at the dawn of the ’90s. Instead of the electronics section, early video game consoles could be found in the boys’ toys aisle at stores. The marketing also swayed aggressively toward men.

“As a result, when women come into these spaces, they’re treated like the women in these ads,” Peloza said of a 1998 commercial for the PlayStation. “The kids that watched those ads, including myself, are now adults in the space and we’re reacting accordingly.”

Paidia is about making esports more accessible and less of a guys’ club. It’s about providing a better solution to women and allies besides turning off their mic during a game, hiding what makes them unique, or not playing at all.

Paidia offers how-to content about gaming topics including tournaments and ranking, as well as industry news, live and on-demand classes and podcasts. Even its art signals a welcoming, inclusive environment. Instead of white, hypermasculine characters armed to the hilt with a female accessory toeing the line between waif and buxom, Paidia has original characters of all sizes, ages and colors. The time is right for this change and 2022 is a year to rebuild, Kenney told me.

A look at some of the original characters you’ll see in Paidia’s portal.

Paidia/Screenshot by CNET

“Everyone deserves to see themselves represented,” Kenney said. “The reality of the world is that many types of people exist and there is a huge discrepancy in their visibility in mainstream entertainment.”

For decades, marginalized communities’ space in a video game was limited to that of a token, a side quest, a caricature or a bikini-clad incentive for a male hero — or they weren’t present at all. The events of the last year — though not new — have breathed life into a movement to make a change in 2022. And gamers aren’t waiting for change. They aren’t waiting for permission. They’re the battle cry. They’re creating change.

RekItRaven says she’s never considered herself a source of hope or symbol of change, but people have come to see her in that light. At the end of the day, while the work is overwhelming, she wants to make online gaming spaces safer for her kids.

“It’s humbling because I’ve always said this was bigger than me [and] it’s true,” Raven says. “I get to look at the two little people I brought into this world, and I just get taken aback because maybe something I did here will stick. I just hope that they’re proud of me.”