The internet is full of terrible corners, but none are as skin-crawling as what you see when you open a new account on TikTok. The app’s freakishly personalized algorithm gets better at knowing what you like the more you use it, so as someone who’s had a TikTok account for nearly four years, mine’s full of cats, hair tutorials, and 15-year-olds with mental health concerns who will grow up to be successful stand-up comedians.

An unsullied For You page whose only knowledge is that you are human will serve you a disorienting combination of two things: hot girls’ butts, and advice on how to steal other people’s viral video ideas.

Why the butts are there is self-explanatory (they get the most views). The latter phenomenon, however, reveals a much darker side of the human condition. What they’re offering are “tips” or “hacks” on how to go viral on TikTok, which is embarrassing in itself but even worse in practice: titles range from “How to Grow Your Account to 1k Followers in 1 Week,” to “10 Video Ideas Anyone Can Use,” or “How to EASILY Produce Video Ideas for TikTok.” That last one gives the following advice: “Find somebody else’s TikTok that inspires you and then literally copy it. You don’t need to copy it completely, but you can get pretty close.”

While the creator behind it is condoning pretty sleazy, algorithm-brained behavior, I have to appreciate his honesty about a practice that has plagued the internet since it’s existed: plagiarism, both the intentional kind that can fall anywhere on the spectrum of “pretty shitty” to “actively evil,” and the kind you do when you’re making content in a system of increasingly lucrative rewards for stealing successful people’s stuff. Though plagiarism is arguably most prevalent on TikTok, it’s even harder to police the plagiarism that happens between different platforms.

Brenden Koerner is used to people using his work as source material. This is typically a good thing: About once a week, he’ll field inquiries from producers hoping to interview him for a documentary or adapt one of his books into a film or a podcast. If they option one of his works, he’ll get a cut of that sale. Earlier this year, the bad kind happened: Someone published a podcast based exclusively on a story he’d spent nine years reporting for The Atlantic, with zero credit or acknowledgment of the source material. “Situations like this have become all too common amid the podcast boom,” he wrote in a now-viral Twitter thread last month.

This podcast series is a shameless rip-off of my @TheAtlantic story from last April. No credit is given and the creator did zero original reporting. He even mispronounces the main character’s name through all 8 episodes. (It’s “kuh-SEE,” not “KEY-see.”) https://t.co/X19tHnSUXF

— Brendan I. Koerner (@brendankoerner) April 11, 2022

Amidst the growing thirst for captivating or sensationalist narratives, several true crime and history podcasts have been accused of plagiarizing written articles without credit over the past few years. Koerner has had this happen to him several times. “If something’s easy or free to access, there’s maybe a general assumption that it’s free to use,” he says. “There are a lot of people who’ve had their hard work repackaged for profit, and I fear it’s ultimately going to be a net negative for the whole ecosystem of people who create and tell stories.”

Plagiarism, it should be noted, is perfectly legal in the United States, provided it doesn’t cross the (often nebulous) definition of intellectual property theft. Movies, music, or works of fiction have robust legal protections against this (recall the zillions of lawsuits between artists for stealing each other’s samples), and Koerner’s Atlantic story is protected under the law as well (in works where the originality or artistry of the author is sufficiently evident, courts will side with the creator), but it often isn’t worth the time and money to pursue legal action.

Yet the definitions of what constitutes IP get murky quickly. You can’t copyright a dance or a recipe or a yoga pose, for instance, and it’s really hard to copyright a joke. You also, for obvious reasons, can’t copyright a fact, which means that in industries where IP law can only do so much, social and professional norms dictate your reputation: journalism, comedy, and academia, for instance, fields in which plagiarism is the among the most cardinal of sins.

So what of the average influencer, YouTuber, or podcaster? Internet posts are, for the most part, not copyrightable intellectual property. Instead, they’re more like a hybrid of journalism and comedy, meaning that social media typically must police itself against thieves.

Meme theft has been the subject of debate for as long as they’ve been around; back in 2015, popular Instagram meme pages like @TheFatJewish and @FuckJerry faced a reckoning over joke stealing, largely from comedians but also from random people who’d made viral tweets and later saw them reposted elsewhere. Fast forward seven years, and the problem hasn’t gone away — in fact, it’s gotten worse. The meme pages, or accounts that curate mostly other people’s content, won. Some have even successfully argued that what they do is an art form in itself.

Jonathan Bailey became interested in the subject of plagiarism in the early 2000s, when he ran a goth literary blog devoted to his poetry and fiction. After a reader pointed him to another blog that was stealing his work, he did some digging and found hundreds of others in the online goth community republishing his writing as their own. “I actually won a crap ton of contests on AllPoetry.com despite never having an account there,” he says. For the past decade, he’s been focused on his blog Plagiarism Today, which tracks current events relating to the subject and advice for what to do if you’ve been plagiarized.

He posits that there are three main eras of internet plagiarism. The first was in the ’90s and early 2000s, when people stole each other’s work because they wanted to pass it off on their own, but didn’t necessarily have a profit motive. The second was in the mid-2000s, when search engine optimization became a widespread practice and sites could make money from crappy, AI-written work that capitalized on the strategic placement of certain keywords. “That came to a halt when Google really started clamping down on low-quality content,” Bailey explains. The third era is made up of the kind that flourishes on social media, where users compete for the most attention-grabbing content in the hopes they might make ad revenue or score a brand deal.

“[Social media] puts a lot of pressure on what is fundamentally a creative process,” he says. “I’ve talked to repeated plagiarists who say ‘I felt pressure to put up this many articles or podcasts or videos.”

It’s easy to argue that social media platforms practically beg their users to plagiarize each other. “The way that YouTube works is that [people] create trends, and those trends are meant to be followed by everyone else,” explains Faithe Day, a postdoctoral fellow at UC Santa Barbara’s Center for Black Studies Research who works with students on data science and digital platform ethics. “But there’s a fine line between following a trend and copying what someone else is doing and saying it’s your own.”

Determining who copied who is a convoluted and often unsolvable problem, particularly when people exist in such varied digital spaces. “A lot of people who plagiarize don’t know that they’re plagiarizing. They don’t know that the thing they’re talking about someone else has already discovered,” Day says.

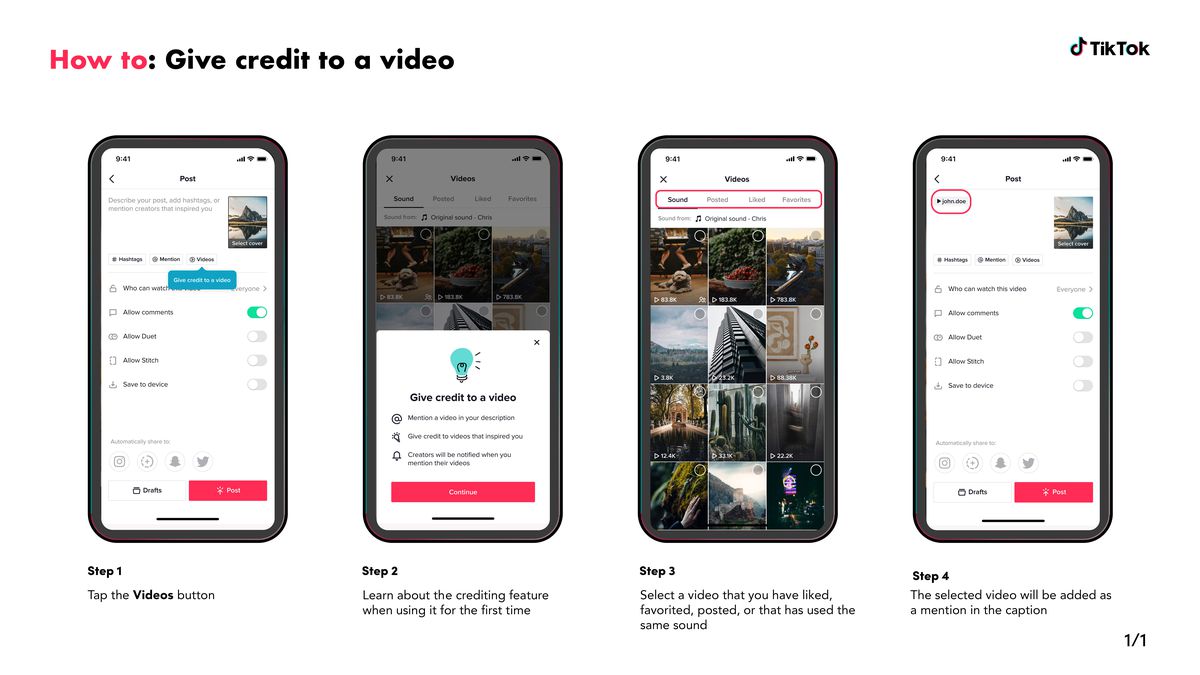

It’s difficult to name a platform where plagiarism is more pronounced than TikTok, whose technology encourages people to react and build off each other’s work, often with little or no acknowledgment of the original creator. It’s become such an issue that last week TikTok announced a new feature that allows its users to credit an existing video when posting their own. “These features are an important step in our ongoing commitment to investing in resources and product experiences that support a culture of credit, which is central to ensuring TikTok remains a home for creative expression,” wrote Kudzi Chikumbu, TikTok’s director of creator community, in the announcement.

TikTok’s new crediting feature.

TikTok

Day sees this most often in instances where popular TikTok creators hop on a trending dance or audio without knowing who the original creator is, thus spreading it to more people for whom the popular creator was the de facto origin. Nowhere was this more clear than in late 2019 and early 2020 when the Renegade dance took over TikTok, despite its choreographer, a 14-year-old in Atlanta named Jalaiah Harmon, receiving none of the credit or clout until months later.

The instance sparked a reckoning on the platform, culminating in a Black creator strike to protest rampant co-opting of the community’s dances and slang. “Recommendation algorithms are engineered to ensure that people who have large followings are being recommended to other users, so there aren’t a lot of possibilities for smaller creators to get recognition,” Day explains.

There has never been quite so much to gain, potentially, by being widely credited as a true originator of a viral moment. Coin a term? Sell it as an NFT. Appeared on a reality show? Launch an OnlyFans. Get a ton of followers for whatever reason? Put your Venmo handle in your bio. Shill for a shady galaxy lights brand or sign with an agent who specializes in squeezing cash out of small bursts of attention.

In a climate like this, people have understandably grown quite protective over their ideas, sometimes to the point of being obnoxious (a fellow journalist recalls a time when a TikToker was angry that she had offhandedly linked to one of their videos without mentioning them by name). There are incentives to passing other people’s work off as your own — incentives, even, to avoid researching whether anyone has done the work before.

“Everybody’s looking for a side hustle, and an easy way to make money is aggregating content,” says Chris Stokel-Walker, a UK-based journalist who’s experienced several of the kind of muddy is-is-actually-plagiarism moments where you end up feeling used and exploited but unsure of whether it’s worth starting trouble. “It does hurt, in a way. It’s like, well why did I spend months researching a story or a book only for someone to saunter along, cherry-pick the best bits, present it in a different format, and claim all the credit? What’s the point?”

While the technology to detect it has improved, it’s far more difficult to weed out plagiarism when it happens in different forms of media: written work that’s turned into a video, a podcast that’s turned into a book. Rather than relying on data systems to tell us when something is stolen, then, plagiarism experts acknowledge that the shift about proper idea attribution needs to happen culturally. “We have to answer that question as a collective society,” Bailey says.

“We need greater understanding about media literacy and internet ethics,” Day says. “It’s about doing the extra legwork, doing a Google search before you reproduce something. But people don’t do that extra work because there’s an assumption that what they’re seeing is a direct reflection of reality, which of course is not always true.”

They also might not be doing it because they have a monetary incentive to remain ignorant. But that’s a more complicated problem, one that can’t be solved with a platform tweak or new crediting system. It has to be widely understood that plagiarism is, for lack of a clearer term, loser behavior. And that begins with all of us.

This column was first published in The Goods newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one, plus get newsletter exclusives.