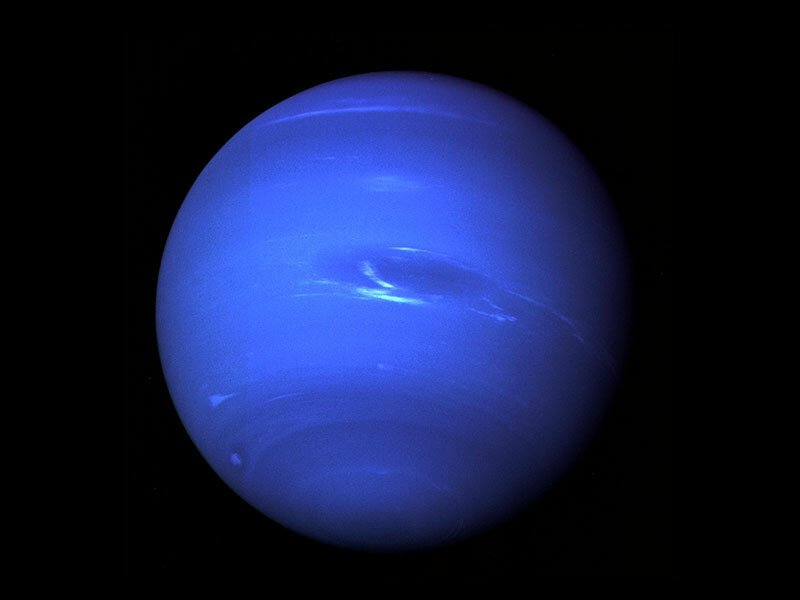

Only one spacecraft has ever visited far-off Neptune.

In 1989, NASA’s Voyager 2 probe beamed back astonishing images of this dynamic world, including an Earth-sized storm with 1,000 mph winds. Since then, planetary scientists have used giant telescopes either on or orbiting Earth to observe uncanny Neptune, the farthest planet from the sun.

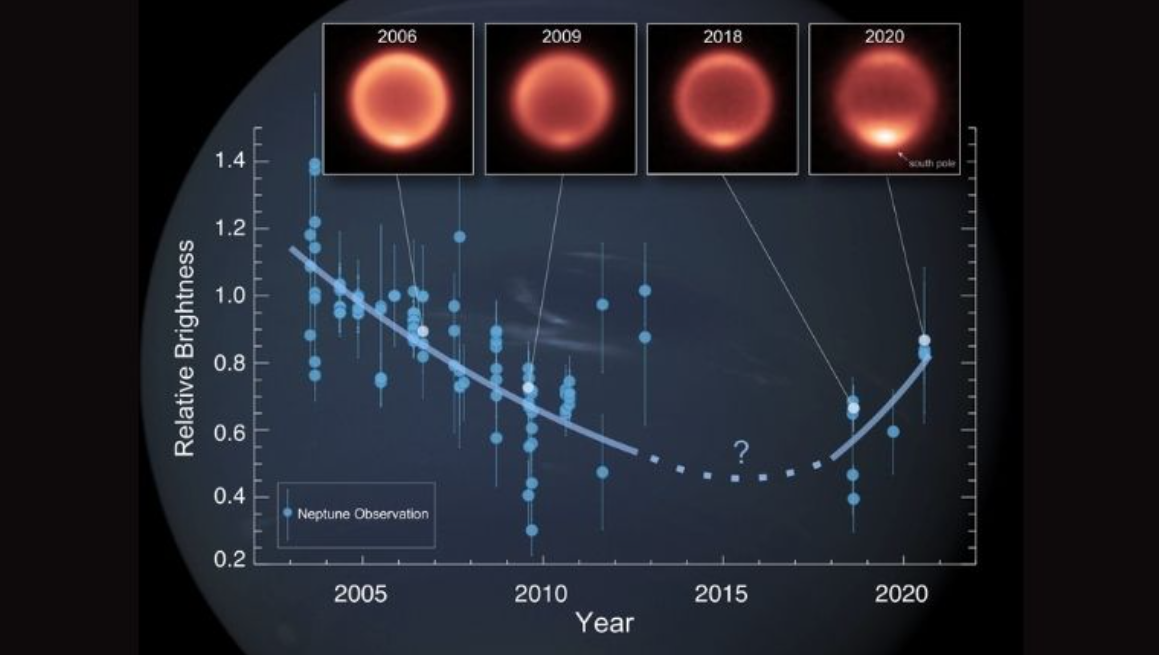

And in the last couple of decades, they’ve watched extreme changes in the planet’s atmosphere. Between 2003 and 2018, average temperatures in Neptune’s stratosphere — a big layer of the atmosphere lying above storms and weather — plummeted by 14 degrees Fahrenheit. Then, between 2018 and 2020, stratospheric temperatures in the South Pole suddenly shot up by a whopping 20 degrees.

“There are lots of very strange things happening on Neptune that we don’t understand.”

“It’s very unexpected,” Glenn Orton, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and an author of the new Neptune research, told Mashable. “There are lots of very strange things happening on Neptune that we don’t understand.”

The findings were recently published in the Planetary Science Journal. In the graphic below, you can see the significant drop in temperatures, followed by a sudden rise after 2018. Neptune orbits some 2.8 billion miles from Earth, so astronomers measured the planet’s temperature change by watching fluctuations in its brightness (in a light wavelength called infrared, which isn’t visible to the naked eye).

Changes in thermal brightness detected on Neptune.

Credit: Michael Roman / NASA /JPL / Voyager-ISS / Justin Cowart

The dramatic changes are unexpected because they’re happening amid a profoundly long Neptunian season. (It takes Neptune 165 years to orbit the sun, meaning its seasons last decades.) Like Earth, Neptune rotates on a tilted axis and thus has significant seasonal changes (due to the differences in sunlight the planet receives). Scientists expected such extreme temperature changes to happen during different seasons, explained Orton. But now they’re happening amid Neptune’s southern summer. What’s more, researchers expected temperatures to gradually warm up during this long summer — not cool significantly.

What could be driving these uncanny, large-scale changes? “It’s elusive,” said Orton. But the research team has some ideas. It’s possible the sun’s 11-year activity cycles may be linked to temperature fluxes in Neptune’s stratosphere. Or chemical changes in the planet’s hydrogen-rich atmosphere may drive these abrupt alterations.

Planetary scientists want to demystify Neptune because they’ve already identified many (over 1,700) “Neptune-like” exoplanets far beyond our solar system. Understanding Neptune means grasping what’s transpiring in other solar systems.

“The Neptune that we see is an exoplanet in our backyard,” marveled Orton.

Neptune as imaged by the Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1989.

Credit: NASA / JPL

To better understand Neptune, Orton and his colleagues need to better see distant Neptune (which is so far away it’s the only planet in our solar system that can’t ever be seen with the naked eye). Fortunately, help is on the way. The James Webb Space Telescope — the most powerful space telescope ever built — is expected to start observing the cosmos in June. Orbiting the sun around 1 million miles from Earth, it operates at extremely cold temperatures (-447 degrees Fahrenheit), which makes the instrument more sensitive to changes in very cold places like Neptune, Orton explained.

What’s more, the United States’ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will soon release (on April 19) its much anticipated Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey 2023-2032, which will assess future priorities for missions into deep space. Will this influential framework suggest a robotic mission to far-off Neptune and Uranus?

“I like the enigmas.”

“We’re holding our breaths and crossing our fingers,” said Orton.

For the foreseeable future, Neptune will likely continue to be mysterious and behave strangely. But, for some, that’s precisely the best part of planetary science.

“I live for things that are unexpected,” said Orton. “I like the enigmas.”