“Whoah, there are so many things happening at Apple.”

That was one of the DMs labor organizer Clarissa Redwine received on Christmas Eve day, not about the latest gadget appearing under the tree — but about worker activism within the company. Some employees at Apple Stores had declared that they were striking on the last minute shopping day, and calling for a consumer boycott, to demand better working conditions for retail workers. While the limited walkout might not have appeared to make much of a splash to outside observers, it caused tech workers and organizers within Redwine’s world to take notice of the activity, and how Apple employee issues were being aired “at so many different levels.”

Every year since Google workers walked out in protest of workplace discrimination in 2018 has been a landmark one for labor organizing in tech. Now, 2022 is poised to contain even more high profile votes, legal actions, and campaigns. There’s one organizing possibility that could help workers wield power and influence over management even more strongly: Answering a central question of tech industry organizing — what is a tech worker? — with an inclusive response.

Workplace actions have the potential to be even more impactful when “tech employees” are identified as all workers at tech companies, from startups to big tech corporations, up and down the supply chain. Warehouse workers, retail representatives, quality assurance or customer support contractors, designers, coders, and everyone else who makes the tech world run, have to work like they’re in it together, labor organizers said.

“The thing that’s really exciting for me is how much we can do together when we are a larger force with numbers,” Redwine, an organizer at the Tech Workers Coalition, and former Kickstarter employee who helped lead the successful union drive there, said. “So to see these lines blurred across the industry, and to see people really embracing cross-role solidarity, is a huge sign that this movement is accelerating and moving in the right direction.”

It all sounds a bit kumbaya in theory, but in practice, this sort of solidarity within tech has already spurred change. Recently, members of the Alphabet Workers Union (AWU) called out Google for providing high-quality, at-home Covid tests to permanent Google employees, but not contractors. It’s put pressure on the tech giant to take a more equitable approach to worker safety. Both the AWU, and a movement at Apple meant to expose inequality in the workplace called AppleToo, specifically make joining the efforts of technical full-time workers, and non-technical, part time, contract, retail or logistical workers, a founding tenet of their organizations.

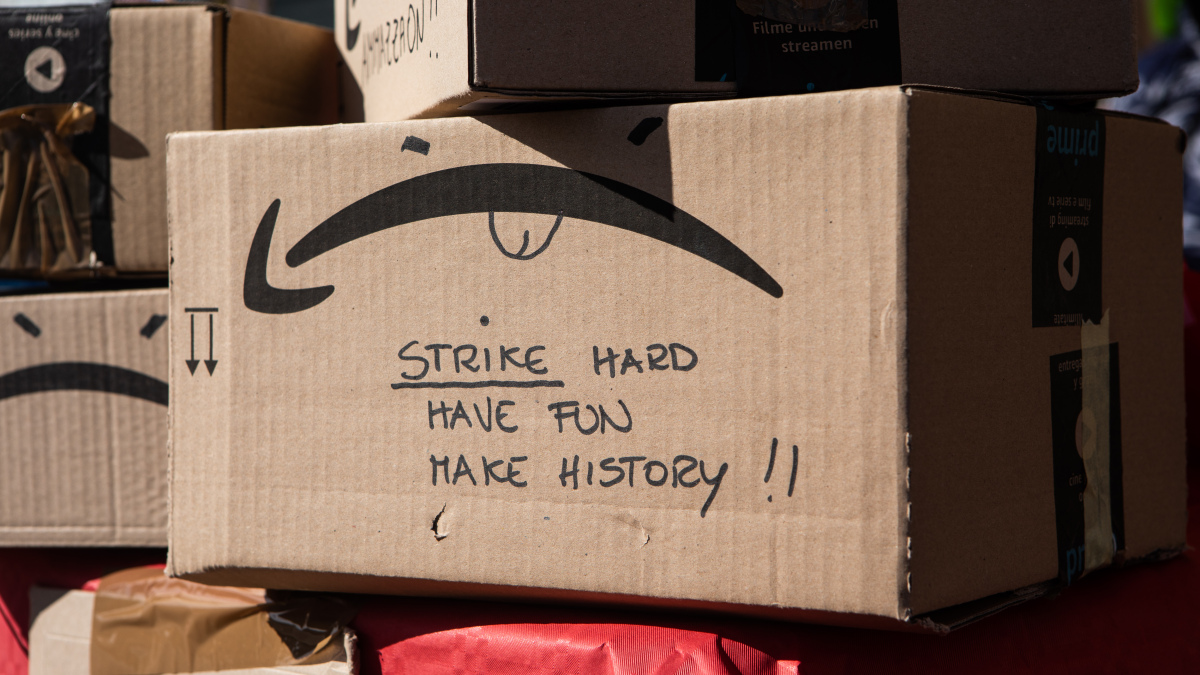

Redwine points to a number of other projects “expressly meant to blur the line between office and non-office, or software engineer and non technical worker, happening across the industry.” In November, writers at the New York Times‘ reviews and shopping website, Wirecutter, went on strike on Black Friday — one of the site’s most important traffic days of the year — in order to agitate for a fair contract. Members of the New York Times Tech Guild, or the employees who run the website, apps, and technical side of the media empire, supported the campaign online and at the picket line. Wirecutter finally reached a contract with management several weeks later.

In the leadup to the Amazon warehouse worker vote to unionize in Bessemer, Alabama, Redwine’s organization used its technical chops to help educate workers. When Amazon posted a misleading website about unions, the Coalition created an annotated version of the site that used facts, absurdity, and website design to counter the anti-union propaganda. The Bessemer union vote failed to pass in April, but the National Labor Relations Board ruled after the fact that Amazon had illegally interfered in the vote. Workers are set to re-vote in 2022, and there are other diverse Amazon organizing efforts taking place. Jess Kutch, co-founder of the advocacy organization Coworker.org, said her organization has been supporting grassroots movements at multiple levels of Amazon, including warehouse and delivery workers, as well as employees like UX designers at headquarters.

“There’s pressure inside Amazon in various parts of the company to organize,” Kutch said. “Workers are trying to build power.”

For the most part, both in recent years and historically, organizing in tech has been stratified. Workers such as those Amazon employees voting to unionize in Bessemer and Staten Island are running campaigns with demands similar to other union efforts outside of tech that focus on issues like wages, benefits, and worker safety. But back at tech office headquarters, worker actions have been focused around workplace equity and business ethics issues, such as not taking government contracts to provide infrastructure for ICE or build AI for the military.

It’s not inevitable that the two will coalesce.

“There would be a big cultural, educational, and class gap between programmers at Amazon and warehouse workers at Amazon,” said Louis Hyman, the director of Cornell University’s Institute for Workplace Studies, who has studied tech organizing in Silicon Valley, said. These gaps have historically stood in the way of organizing movements, he added. Kutch is “not yet clear” on whether Amazon warehouse workers consider themselves tech workers.

But the fact that office workers are standing up to management at all means that history might not have such a strong hand in writing the next chapter. General Electric factory workers went on strike in the 20th century, but “there weren’t strikes in the GE management suite to make GE treat their workers better or not build bombs,” Hyman said of how organizing seems to be permeating in places it has not before.

When Kutch worked with Google employees in the early days of organizing in the mid-2010s, Google employees were concerned about the contractors and vendors such as cafeteria workers and bus drivers, but they didn’t think they had their own beef with management or rights issues.

“That’s not the case anymore,” Kutch said. Executive decisions regarding government contracts have shown employees that they may have less sway than they thought, despite company talking points about purpose-driven missions. Some tech employees now “see themselves as workers, and they understand that they only have so much power in their companies, despite what their paycheck might be, and that the only way to actually have power is to join together.”

It’s possible that the organizing tool of mutual aid funds could help further that cause. Mutual aid funds are collections of money that union advocates use to financially support individuals who are organizing their workplace, and who might need a financial safety net if they face retaliation from their employers. The money comes from professional peers. Through mutual aid funds, highly compensated workers can extend a hand to whoever needs it, whether that’s engineers, QA contractors, or logistical employees.

Several of these funds have sprung up in recent years, and each has different criteria for who can apply, and committee members that award the funds. Kutch’s organization is currently raising money for its third round of awardees for the Solidarity Fund, which gives out $2,500 to tech workers they select. There is a fund called Tech Workers for Tech Workers, meant to support gig economy workers, like rideshare drivers. And when workers at Blizzard Activision announced their intention to go on strike in December, they also launched a StrikeFund and called on “our peers in the gaming industry” to finance it to cover lost wages.

The funds have already demonstrated the ability to connect, and perhaps solidify, groups organizing within tech. In creating the Solidarity Fund, Kutch said the organizing committee had to actually define a “tech worker” in order to determine who would qualify. They decided “all workers in the tech industry, regardless of job function” were eligible. So even establishing the fund laid the groundwork for solidarity.

Both contributing to and receiving funds could be re-enforcing those bonds. Kutch said that she was surprised when the organizers of the Apple retail strike tweeted a link to the Solidarity Fund, because her organization had not actually been working with them. But she saw in real time that Apple employees from across the organization were making “significantly large” contributions, though Kutch did not specify a dollar amount.

“It’s really interesting that there are now these lines of mutual recognition and solidarity between different kinds of workers,” Hyman said.

Kutch has also observed that the funds do more than provide financial support. For workers who are under extreme pressure both at work and perhaps at home, it’s a validation that their work is important.

Google workers in 10 countries form union alliance: ‘We will hold Alphabet accountable’

“I saw that a lot of people were just affected by just having some third party recognize their sacrifices and their efforts,” Kutch said.

Hyman remarked that logistics workers like Amazon warehouse employees and drivers are holding an immense amount of power right now thanks to the way the supply chain has faltered. Meanwhile, social media companies like Facebook and TikTok need a steady stream of content moderators to keep their platforms from devolving into depraved chaos. Gaming companies like Blizzard need QA testers to make sure their games don’t break, media companies need tech workers and creatives alike to churn out content, and everyone needs the highly paid — but no longer so content — programmers and engineers to maintain and build the internet.

And while organizing had been siloed in the past, there’s a possibility things could be different in the years ahead.

“Cross class solidarity is incredibly powerful and meaningful, it’s actually how we’re going to build worker power in the tech sector,” Kutch said. “Our fates are all tied together.”