It’s not just another perk in a benefits package — remote work could fundamentally reshape the urban geography of the United States.

Where we live has been dictated by where we can find a good job. That truism has defined much of where Americans reside — clustered in and around lucrative job markets.

In particular, “superstar cities” have been a defining technological advancement. According to a 2018 article by economist Richard Florida, “the five leading metros account for more than 80 percent of total venture capital investment and 85 percent of its growth over the past decade.” Another economist, Enrico Moretti, recently noted that “the ten largest clusters [cities] in computer science, semiconductors, and biology account for 69 percent, 77 percent, and 59 percent of all US inventors.”

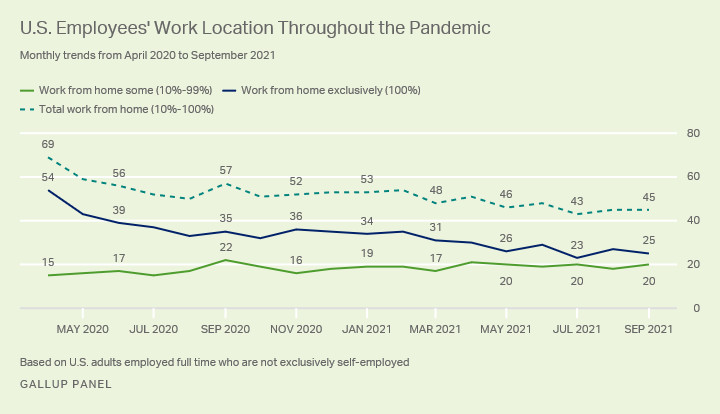

Remote work could change that.

While only 37 percent of jobs could be performed remotely full time (according to two University of Chicago economists), those jobs have outsize purchasing power (accounting for 46 percent of all US wages by the same estimate). When people with these jobs congregate, they provide the necessary demand for a vast array of service sector jobs, from nurses and lawyers to teachers and taxi drivers. This is hugely important — it means that remote work could expand the choices of where to live for millions of Americans, not just those who have the option to work from home full time.

Imagine, for example, that you’re a human resources manager at a tech firm in San Francisco, married to a baker and paying $2,800 a month for a one-bedroom apartment. With remote work, you could instead move to be closer to your family in Nashville or Orlando, and save a bunch of money on rent alone. And when you move, you’ll take your family and your demand for services with you to those locations, opening up opportunities for other workers — including, say, your spouse, who could confidently move with you and open a bakery catering to other new transplants.

To be sure, there’s good reason to believe that very little of this will happen.

Productivity is an open question and perhaps the most important one. Remote work doesn’t have one clear effect on workers’ productivity, evidence from economists Emma Harrington and Natalia Emanuel shows. Productivity losses or gains under remote work are likely to be different industry by industry, firm by firm, and role by role.

But if, on the whole, firms that choose to work in-person outperform those that are remote, it could push the equilibrium back to where we were before the pandemic. That’s what Moretti predicted to me back in April 2021: “The moment you start losing that creativity and productivity, that’s when both the employer and employee have something to lose from this decentralized application.”

Moreover, agglomeration economies — “the tendency of employers and workers to cluster” in big cities — are very powerful. One of the big reasons this happens is because of matching between labor demand and supply. Particularly for highly specialized workers, you want to live in a place with a lot of firms you can work for, so that you can bid up the price of your labor. And for firms, similarly, they want to be in a place with tons of workers they could hire for specialized roles, so they can find the best one.

For remote work to delink where people live from where they work, it’s likely not enough for just one biotech firm to decide its employees can work from home full time. A bunch of firms in that industry would need to make that shift.

If that happens — one economist thinks about 20 percent of jobs will realistically go fully remote in the long run — there will be massive implications for where Americans live and work, presenting new challenges and solutions for the housing crisis, climate crisis, and our political institutions.

Post Contents

Remote work and housing markets

America’s “superstar cities” are lucrative labor markets — but the price of entry has become the cost of living, namely, the price of shelter. Housing costs have skyrocketed in these places, because supply has been artificially constrained by the labyrinth of regulations and veto points in the housing development process.

Fixing this process is paramount, expert after expert has maintained. And while there has been some progress in recent years — notably on the West Coast — as of May 2021, the country has a shortage of about 3.8 million homes, with the problem concentrated in the metropolitan regions with the most valuable labor markets.

Remote work could relieve some of the upward pressure on housing in these cities, in part by diffusing demand throughout the metro-suburban region. One study, for example, showed that a shift to working from home would “directly reduce spending in major city centers by at least 5-10 percent relative to the pre-pandemic situation.” And economist Matt Delventhal found that an increase in remote work in the Los Angeles metro area would lead average real estate prices to fall: “As many workers move into distant suburbs, prices in the periphery increase. However, these price increases are more than offset by the decline of prices in the core. … In the counterfactual where 33% of workers telecommute, average house prices fall by nearly 6%.”

Fully remote work, meanwhile, could make it possible for people to avoid the high housing costs of places like Seattle or Boston entirely, while still accessing the jobs they offer.

By reducing the demand for housing in these major cities, the upward pressure on housing costs could ease. It also means that demand could be spread more equitably across the United States. We saw this dynamic begin to play out during the pandemic as rents rose in more affordable cities like Baltimore and Dallas. But to accommodate that demand, cities need to make it easy to build more homes in these locations, otherwise rents will follow the same pattern as in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC.

While cities like Austin, Phoenix, and Atlanta are some of the natural inheritors of superstar city-dwellers seeking more affordable but still urban living, there is also an opportunity for smaller cities to benefit from a shift to fully remote work. One is already trying to seize it.

Like many American cities, Tulsa, Oklahoma, struggles with population growth and attracting high-wage workers. In order to combat this, a program called Tulsa Remote was launched offering $10,000 grants and “numerous community-building opportunities” to fully remote workers to move to Tulsa for a full year.

“Tulsa did not just offer the $10,000,” Upwork chief economist Adam Ozimek told Vox. “Tulsa has also worked to build community for remote workers and create lots of local amenities. Tulsa was also the first to do it and this has been unequivocally good for Tulsa … but I would be surprised if anybody found out [$10,000] works out by itself. No one’s going to make lifestyle decisions around $10,000.”

The Economic Innovation Group released a report in November outlining the results, finding that the program “is expected to be responsible for 592 full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs and $62.0 million in new labor income for Tulsa County in 2021 alone. In total, for every dollar spent on the remote worker incentive itself, there has been an estimated $13.77 return in new local labor income to the region.”

Making housing more accessible is great, but the impact of remote work won’t be cheaper house prices for everyone. While people who formerly lived in urban areas and can now move to the periphery would likely see a reduction in their housing costs, those who already live there, or who live in more affordable cities, would see their housing costs increase. While the average cost of housing would decline in this scenario, the differential impacts are important for policymakers to consider so that they preempt unwanted displacement by liberalizing zoning laws.

Remote work and the climate

Density is a carbon mitigation tool. Densely populated areas can benefit the most from transit and walkability. They can also reduce energy costs. If fully remote work becomes possible as the vast majority of American localities plan for sprawl and electric vehicle growth remains sluggish, it could exacerbate the climate unfriendliness of our built environment.

“Both logic and empirical evidence suggest that developing more compactly, that is, at higher population and employment densities, lowers VMT [vehicle miles traveled]. Trip origins and destinations become closer, on average, and thus trip lengths become shorter, on average,” reads a report by the National Academies. Whether remote work has a negative carbon footprint relies on what types of communities people move to and how that influences their energy consumption and driving behavior.

Most evidence thus far has shown that as people have moved over the last year, they’ve generally stayed within the same metro region but tended toward the suburbs. In May, Stanford economists Arjun Ramani and Nicholas Bloom termed this the “donut effect,” with the hollowed-out center representing the declining demand for urban life during a pandemic that forced many urban amenities to shutter. This effect is concentrated in the 12 most-populous metro areas.

But these don’t have to be your father’s suburbs. Recode’s Rani Molla has reported on the “urbanization of the suburbs,” writing that while people are leaving cities for the suburbs, they are bringing their taste for city amenities with them — these new suburbanites like walkability and access to a diverse array of restaurants and stores. If suburbs become more walkable and transit-friendly, and our land use laws allow for mixed-use development such that housing can be built near job centers, shopping centers, and schools, it could mitigate the harms of this change. As always, every locality should stop subsidizing the cost of parking and make it easier to take climate-friendly transportation.

The Stanford researchers note there isn’t a significant amount of movement happening between metro areas, which indicates that at least so far, hybrid remote work is a more likely outcome than a large number of workers going fully remote.

Remote work may need more time for its true impact to be felt. While many people may have moved to the suburbs in a state where they already resided, that decision was likely influenced by their uncertainty around how long remote work would be permitted in the pandemic and after.

The carbon impact of fully remote work is highly uncertain. There are many reasons to think that it would be negative: People moving toward less dense areas without access to transit networks and into a land-use legal framework that incentivizes large single-family homes and sprawl does not bode well.

For some, remote work could eliminate commuting, which is a significant contributor to workers’ emissions. As the Atlantic’s Derek Thompson explained in a recent interview on Vox’s policy podcast The Weeds, “a culture where Zoom is considered a perfectly decent replacement” could curb the most carbon-intensive travel of all: air travel. Depending on a lot of factors, the reduction in flying could outweigh any increase in commuting by car.

It’s also possible that focusing on urban geography as a major part of the solution to the climate crisis is misguided. “My bet would be that the energy sector-specific changes are more important than the future of remote work,” Thompson said. That is, pushing the US to electrify vehicles and get more of its energy from low-carbon sources like nuclear, wind, solar, or hydropower is likely far more important than marginal changes in density.

Remote work and politics

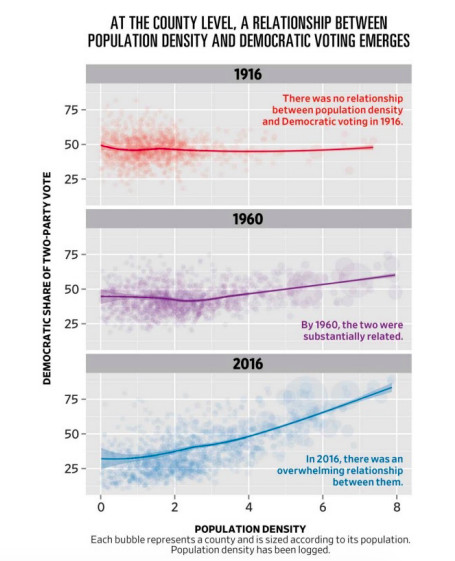

In recent years, Democrats have grown increasingly concerned as college-educated voters cluster in heavily liberal-leaning states. This exacerbates an Electoral College and Senate advantage for Republicans, whose constituency is more evenly distributed across more of the country.

Will Wilkinson outlined many of the political harms that have accompanied urbanization in a Niskanen Center research paper, “The Density Divide: Urbanization, Polarization, and Populist Backlash.” He argues that polarization has been amplified by “the self-selection of temperamentally liberal individuals into higher education and big cities while leaving behind a lower-density population that is relatively uniform in white ethnicity, conservative disposition, and lower economic productivity.”

It’s not just that there are higher-paying jobs in Los Angeles than in Youngstown, Ohio — the nation has been segregating based on people’s openness to experience and liberal attitudes.

Remote work could change some of this. While some people might still sort based on those characteristics and stay in deep blue states, others will find there are enough liberals in cities like Bozeman, Columbus, or Austin, to make do. Others still could forgo these preferences in favor of slashing their cost of living, deciding that it’s fine to live in a neighborhood of the opposite political party as long as you can afford a pool.

As Arizona’s population has grown in part from California emigrants (one study showed that 23 percent of all Arizona immigrants came from California) Democrats have netted benefits, winning both Senate seats and the state’s 11 Electoral College votes in the 2020 presidential election. Increasing numbers of college-educated voters could advantage Democrats further in the state, as well as in places like Georgia, Florida, and Texas.

But the impact of more remote work might not be that straightforward: In August 2020, Thompson theorized that a “demographic shift could reshape American politics. A more evenly distributed liberal base could empower Democrats in the Sun Belt; accelerate the Rust Belt’s conservative shift; strengthen the moderate wing of the party by forcing Democrats to compete on more conservative turf; and force the GOP to adapt its own national strategy to win more elections.”

But an influx of well-educated, highly paid coastal expats could affect the political trends of existing residents in other, unexpected ways. Coastal emigrants’ views might change because part of what was making them Democrats was living in diverse and dense communities.

There’s also a chance that in many of these states, existing institutions could stifle liberal sentiment.

At the local level, as long as these states’ governors and statehouses remain Republican, state preemption laws could hamstring localities from enacting policies that reflect an increasingly liberal electorate. Republican states have stepped in to make it illegal for localities to tax plastic bags for environmental reasons, to prevent localities from extending anti-discrimination protections to LGBTQ people, and Indiana attempted to cripple a bus rapid transit system in Indianapolis.

As blue cities gain prominence in red states, it is likely to set up showdowns over the limits of municipal power. These fights will only intensify if left-of-center voters flock to electorally vital red and purple states.

Another important political trend is that newcomers will trigger NIMBY sentiment wherever they go. NIMBY-ism is a product of scarcity, not a deficiency solely found near the ocean, and as higher-income Americans move where their dollar goes further, existing community members are likely to balk at the changes.

Californians moving to Texas and putting in offers 60k above asking price GO AWAY

— Tiger Lily (@TigerLilyHarv) December 19, 2021

As the New York Times’s Conor Dougherty reported last February, “The Californians Are Coming. So Is Their Housing Crisis.” Locals are angry, Dougherty writes: “in Boise, ‘Go Back to California’ graffiti has been sprayed along the highways. The last election cycle was a referendum on growth and housing, and included a fringe mayoral candidate who campaigned on a promise to keep Californians out.”

Localities have the opportunity to reduce the economic costs of newcomers and preemptively bring down the temperature by liberalizing their zoning laws and investing in market rate and affordable housing as well as enacting anti-displacement measures in order to reduce the conflict. But some conflict is inevitable; as one dispatch from East Austin recounted, residents of a “new luxury building” began calling the police on a neighborhood tradition.

This past year shows that government can have a large role in shaping how remote work plays out. Expanding broadband access to ensure that the ability to do remote work is equitably distributed, liberalizing zoning laws, investing in amenities to attract knowledge economy workers, and ensuring that the gains from growth do not solely accumulate to the most well-off — that’s all in policymakers’ hands.