Scientists detected water on the moon, and for the first time they can say they literally found it while on the lunar surface.

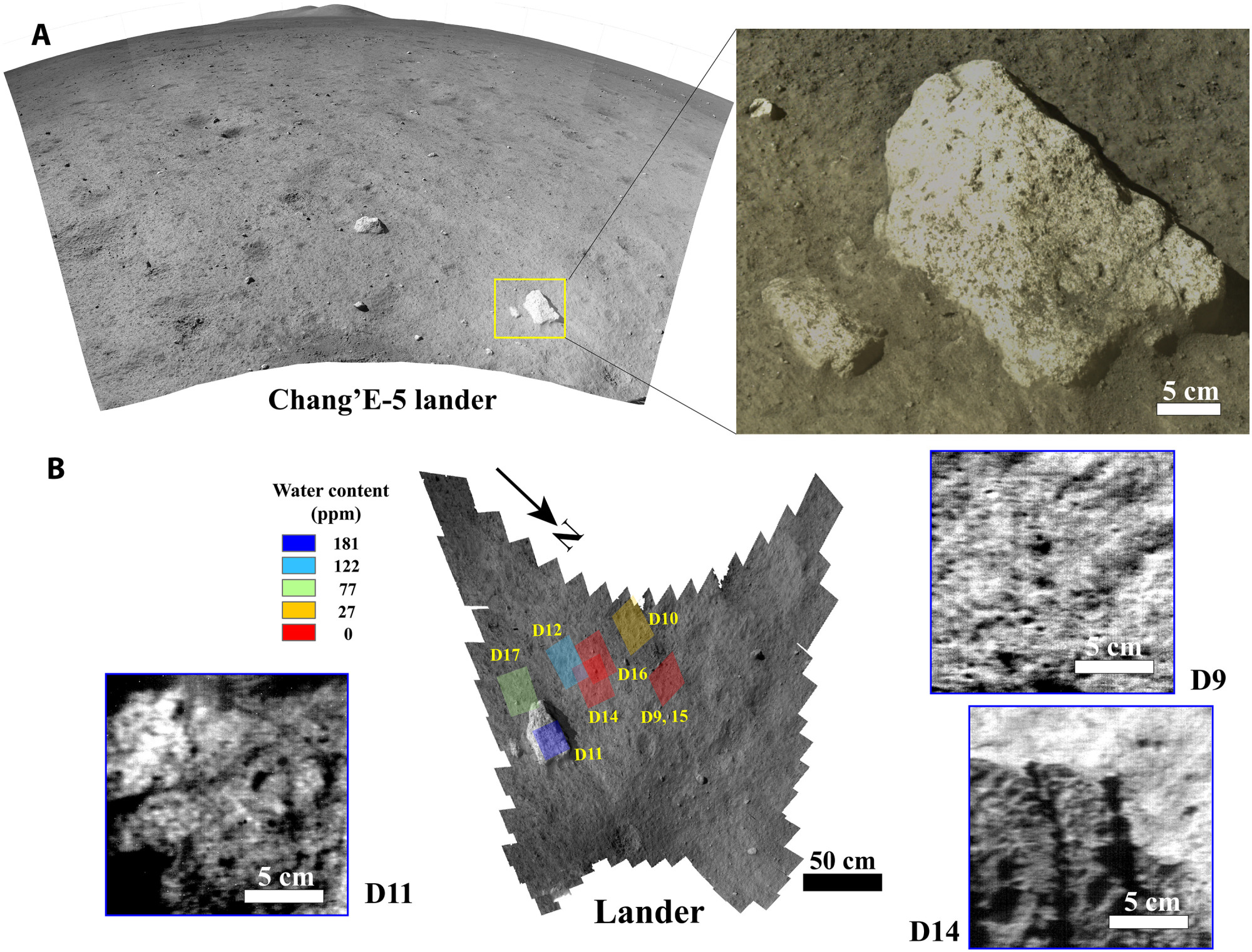

A Chinese lunar lander returned more than 60 ounces of soil and rock samples from its trip to the moon in December 2020. But before Chang’E-5 arrived back on Earth, the spacecraft used an onboard instrument to take measurements there on the spot. Based on the readings, scientists about 239,000 miles away on Earth knew it had likely encountered water.

Water is a rare resource in deep space. Given that it’s a vital, life-sustaining ingredient, the scarcity of it beyond Earth presents an obstacle for people to explore space. Scientists have been interested in whether the moon’s tiny bit of water could be tapped for astronauts to use while away from the planet for a long time.

A research team, led by scientists at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, saw signs of water in the probe’s data, identifying H2O molecules based on their distinct spectral reflectance, a measurement of how something reflects or absorbs the sun’s radiation. The study was published last week in Science Advances.

The Chang’E-5 detection shows there might be more water on the moon than expected, said Matt Siegler, senior scientist for the Planetary Science Institute, a nonprofit based in Tucson, Ariz.

“I’m sure there are a lot of American scientists who are jealous that we didn’t have the lander on the moon to do this measurement,” said Siegler, who was not involved in the study. Siegler will be part of NASA’s Artemis team for its rover mission next year to drill for ice at the moon’s south pole.

Ice near the lunar north and south poles show a shift in the moon’s axis

People’s understanding of lunar water has increased in recent years. When the Apollo astronauts came home in 1969, they believed the moon was completely bone dry.

In the late 2000s, a number of missions, including the Indian Space Research Organization’s Chandrayaan-1, found signs of hydration on the sunlit surface but couldn’t definitively say whether it was H20, or hydroxyl, water’s close chemical relative. Casey Honniball, a NASA postdoctoral fellow, described the latter chemical as something akin to drain cleaner.

Previous missions over the past two decades, such as NASA’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, found ice in the hard-to-reach craters around the moon’s poles that are permanently in shadow. Scientists also reexamined the famous Apollo moon samples in 2008 and found water molecules in glass beads and minerals within them. That discovery was somewhat controversial, though, as some were skeptical of whether the water came from the moon or moisture contamination in Houston.

Then in November 2020, a month before the Chinese lander detected water from the surface of the moon, NASA announced it could indeed confirm water was in a sunny part of the moon — without going there. Flying a jet up to 45,000 feet, NASA used the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, or SOFIA, to pick up the distinct wavelength signals of water molecules. The telescope finding suggested water might be widespread on the moon, not just frozen at its poles.

A researcher looks at lunar soil brought back from the moon by China’s Chang’E-5 probe.

Credit: VCG/VCG via Getty Images

Many previous measurements have seen potential water, but none of those studies occurred on the moon itself — until now. The difference, Siegler said, is that spectral reflectance data has to be corrected for the temperature of the object to figure out how much water is in it. Otherwise, heat from the moon’s surface could change or mask the reflected light features. But it’s hard to know the precise temperature of a target at an extreme distance, he said.

“That’s what’s kind of significant about this one on the lunar surface,” he said. “You know that (specific) rock, and they’re able to measure the temperature of it, and there’s none of this ambiguity.”

Chang’E-5 didn’t find lagoons, gushing rivers or cascading waterfalls in the previously unexplored area. Think much smaller: traces of water in the soil where it landed, a region perhaps ironically referred to as the Oceanus Procellarum, or “Ocean of Storms.” Researchers believe that water was likely formed by solar wind, the gasses flowing off the sun. When the solar wind, which has hydrogen atoms, hits the oxygen in the moon’s soil and rocks, it sometimes makes water.

A moon rock from the same location contained a higher concentration of water than the soil around it, suggesting it had another water source — not just solar wind. The pumice-like rock fragment may have broken off from an older volcanic rock deep within the moon and ejected to the landing site, the researchers said.

A figure in a new study published in Science Advances depicts water content at the Chang’E-5 landing site.

Credit: LIN Honglei

Parvathy Prem, a scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, said she was still smiling days after reading the new study.

“Just as interesting as the rock itself is that the region around it seems to be drier,” she said in an email, an observation that raises more questions about the different ways water is forming and staying on the moon.

Despite the lander’s detection of water, it wasn’t much. Some of the driest places on Earth, such as the Antarctic Dry Valleys, usually have soil moisture content ranging from 0.2 to 5% water, Prem said. The moon rock had about 0.018%, and the nearby soil had just 0.012%, according to the study.

Chang’E-5 was the first moon mission to collect and return material since 1976, when the Soviet Union’s Luna 24 probe brought back samples. The last time NASA retrieved moon rocks was 50 years ago in 1972.

It’s much easier and more precise to study a single moon rock up close in its environment than with a telescope, Siegler said.

“You’re not going to measure that from Earth,” Siegler said. “If America wants to do this kind of science, we have to be on the moon.”