Employees want to work from home. Their bosses, however, can’t wait to get back to the office. Knowledge workers think being remote makes their jobs better, while managers worry the arrangement could cause the quality of work to suffer. But in scapegoating remote work, companies may be disguising the real scourge of creativity right now: too much work.

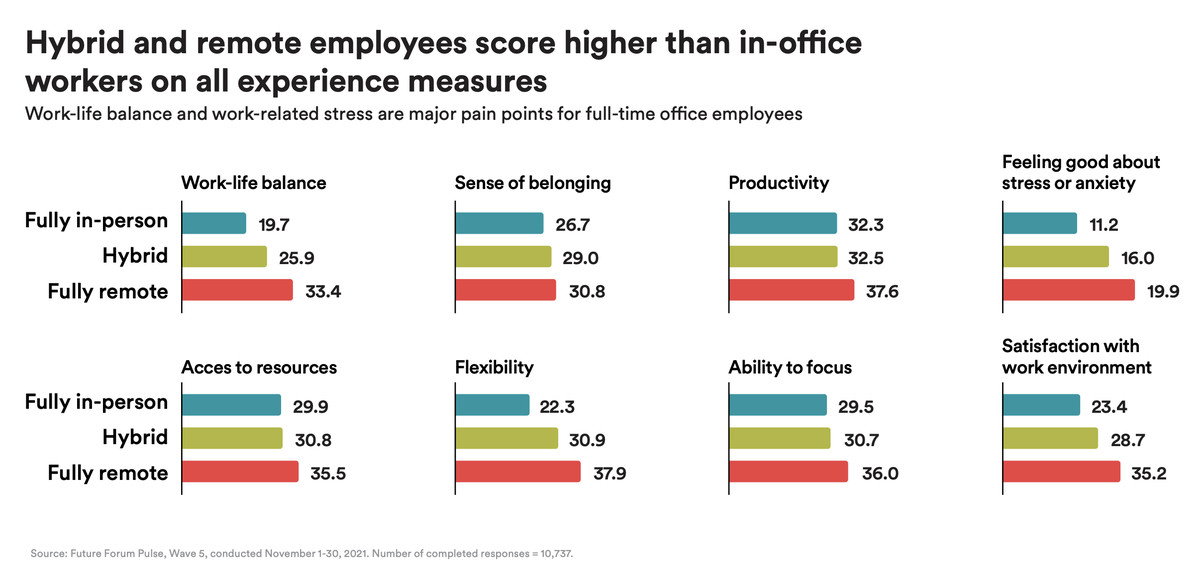

Executives were nearly three times more likely than non-executives to say they want to return to the office full time, according to Slack’s Future Forum Pulse survey. The report found that while nearly 80 percent of knowledge workers want flexibility in where they work — citing benefits ranging from work-life balance to lower anxiety at work and a better sense of belonging — their employers think that the arrangement will lead to a variety of ills, diminishing the company’s collaboration, creativity, and culture. These concerns track with another recent report from Northeastern University that found that more than half of C-suite executives were concerned about their workforce’s ability to be creative and innovative in a primarily remote work environment.

As the worst effects of the omicron variant start to wane, companies will again start to make noise about bringing people who’ve been working from home on their computers for the last two years back to the office. Thanks to an incredibly tight labor market, however, these employees have more leverage than they typically do to get what they want. How this plays out will shape how work is done for years to come.

One issue is that some employers’ concerns with remote work may be baseless.

“It seems to be the prevailing consensus, at least if you ask managers, that, ‘Oh, if you’re all remote, it has to be bad,’ and hence you have to bring people back to the office,” said Christoph Riedl, an associate professor at Northeastern University who’s been studying team collaboration and processes for nearly a decade. “We can directly compare the performance of teams that work remotely versus teams that work face to face, and we generally find no difference with regard to team performance.”

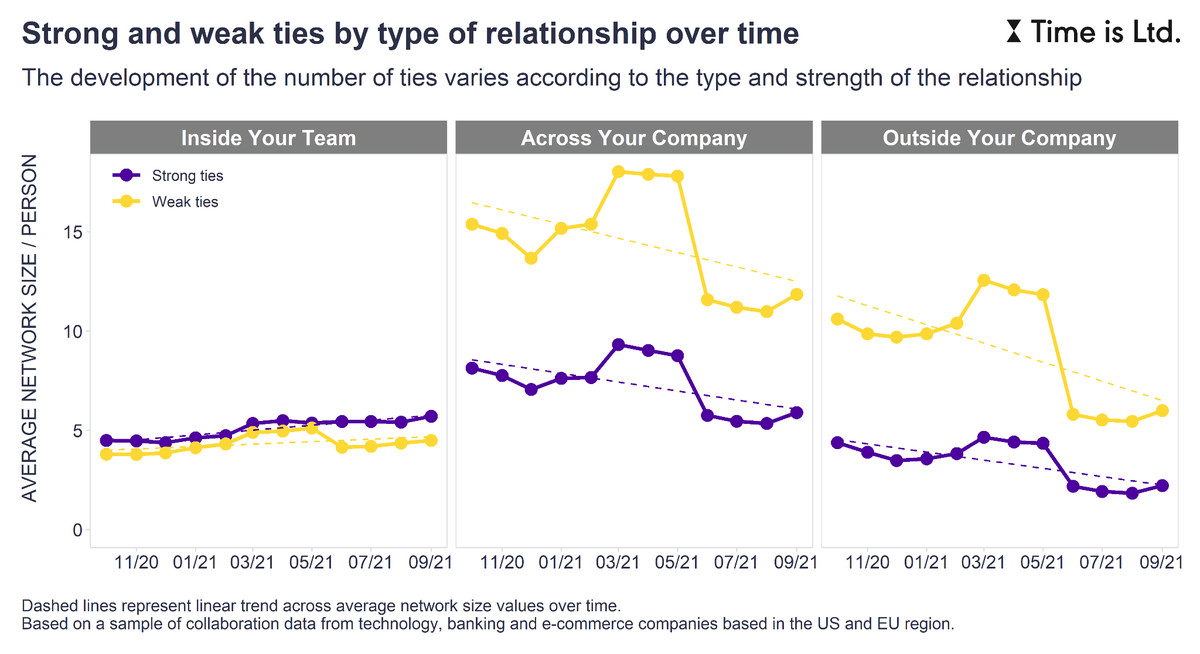

What is certain, and what’s the cause for a lot of this concern, is that our work networks are shrinking. Observed data from both Microsoft and employee engagement platform Time is Ltd. has found that workers are communicating with fewer people at work outside their direct teams. While not a silver bullet for innovation, this type of cross-department conversation can help break down silos and encourage novel solutions. But remote work isn’t the main reason keeping these interactions from occurring: The problem is there’s not enough time for them to happen. In other words, we’re talking to fewer people not because we’re working from home, but because we’re working too much.

Time is Ltd.

“More directly causal of people’s use of time and available hours in the day is the workload, and not the being remote,” Denise Rousseau, a professor of organizational behavior at Carnegie Mellon University, told Recode.

“I do think there’s a tendency for people to attribute one problem to another cause just because they co-occur, saying, ‘We’re working at home, that’s why we’re not innovating,’” Rousseau said. “Our task lists are high, and our headcount is down. That’s another really good reason for not innovating.”

As people have quit their jobs or stepped out of the workforce, in what’s called the Great Resignation or the Great Reshuffling, those left behind have had to pick up the slack. Two-thirds of workers said their workload has increased “significantly” since they started working remote (read: since the start of the pandemic). More than half of those who stayed at their jobs reported taking on more responsibility when their coworkers left, with 30 percent struggling to get the necessary work done, according to a survey last summer by the Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM). People are putting in longer hours, sending and reading more email, and have less time to focus, according to data from Time is Ltd.

“Even before the Great Resignation, if someone were to leave in a department, oftentimes the key tasks would get shared among others in the department until they found a replacement,” SHRM knowledge adviser John Dooney told Recode. “The challenge [now] is there’s a higher percentage of folks resigning, therefore there’s more work to be distributed, and it’s just taking longer to hire people.”

That shortfall can be seen in our communication with wider networks of people at work.

“There’s no time for chitchat, there’s not a time for that interaction that would occur naturally,” Dooney said.

As if increased work-related work weren’t enough, pandemic-related obstructions like lack of child care and smaller social support systems have caused many people to have more work outside of paid work.

“They have more work from their job, and they have an extra role of armchair public health experts,” said Dana Sumpter, associate professor of organization theory and management at Pepperdine University, referring to the many new hats the pandemic has forced people to don. The situation is especially severe among women, who are more likely to take on an outsized share of child care and labor at home. “They’ve made the sacrifice of allowing work relationships to decay or even end because they have finite time and energy and attention.”

People everywhere are burnt out from the pandemic and are doing their best to get by. As Brandy Aven, a professor of organizational theory, strategy, and entrepreneurship at Carnegie Mellon, put it, “When we’re under threat and everybody’s still filled with dread, people will retreat and get very tribal and they hunker down. That’s what we’re seeing.”

Responses indexed on a scale of -60 (very poor) to +60 (very positive). Source: Future Forum Pulse survey

What does seem to be providing workers some solace, according to the Slack survey, is the very thing executives are worried about: remote work. While there’s certainly room to make remote work better as far as maintaining collaboration, creativity, and innovation, the more pressing issue is lightening our workloads.

That means either hiring more people or lessening the amount of work for existing employees. It would require separating the mission-critical from the nice-to-haves in order to give people the breathing room to talk to those outside those it’s absolutely necessary to talk to.

Once we have a little more time and space, we can focus on how to encourage collaboration, creativity, and innovation in a remote setting. If executives want to make the quality of work better, they might want to take a look at the quantity of work they expect. If they want to make remote work better, there are better places to start than the office.